Mental Health Through Time

Thousands would flock to Bedlam to spectate at the “wonders” housed there; the amusement attraction of London. Residents could be found in cages and chained to walls much like captive animals.

By Jessica Young, Featured Writer.

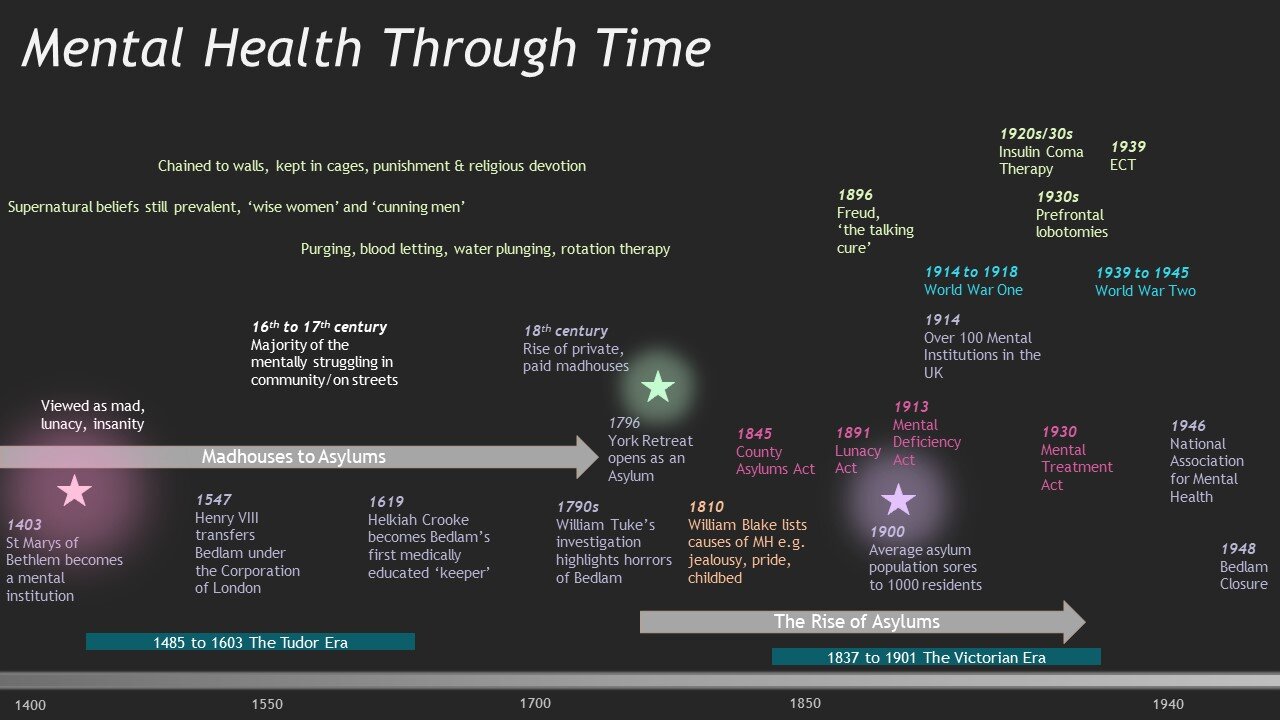

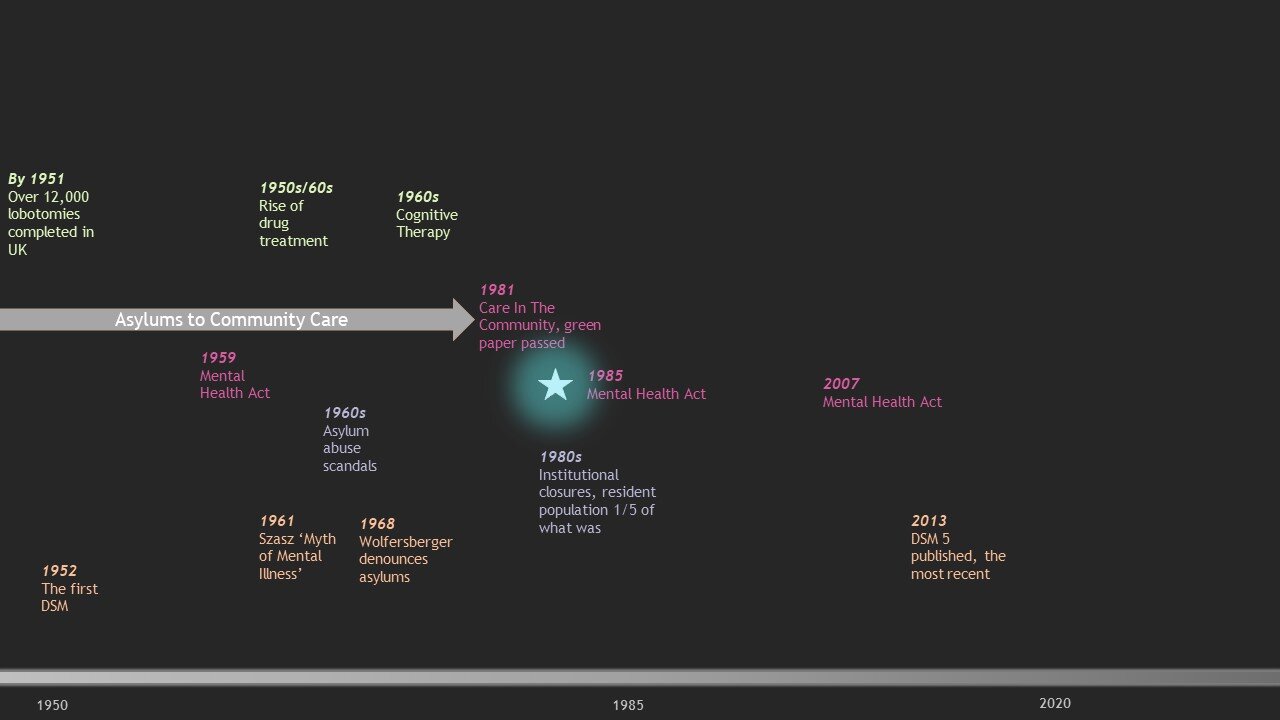

This article provides an overview of some of the significant developments and changes relating to the recognition and experience of mental health struggles, from the rise of Bedlam to present day. Since the perceptions of madness and lunacy, ideas surrounding our mental states have evolved greatly. Over the years there have been changes in the management of mental health through legislation; fluctuations in institutional approaches to individual’s care; and advances in the treatments and interventions for those struggling.

The development of the mental health climate that we currently know has been intertwined with complexities and multiple factors. Our perceptions as a society have adapted and evolved over time and such, the experiences of the mentally unwell have changed. Today there is still a veil of stigma and misunderstanding that drapes over individual experiences of mental health, though it is important to utilise our hindsight and recognise the substantial developments.

A visual representation of the developments and challenges throughout mental health progression. Content was sourced from Havard and Watson (2017), and Historic England (2020, a).

Legislation shapes many aspects of our society, for example providing a framework for infrastructure and understanding to be built upon. By the same token, societal perceptions and approaches of the time mould the laws passed as legislation; it is a two-way interaction. There have been multiple laws passed in-relation to mental health, each reflecting a development in the way society perceived, managed and treated individuals at the time.

1845 Lunacy and County Asylums Act

The rise of the asylum in the UK was in-part due to the legal requirement to have an asylum in every county, alongside the setting up of the lunacy commission to oversee operations. This resulted in a mass increase in the population of the institutionalised mentally unwell. Prior to this, many institutions had run privately such as the private madhouses of the 18th century. This change reflected the Victorian era of structure and categorisation, where the mentally unwell were identified and contained.

(County Asylums, 2020)

1890 Lunacy Act

Highlighting the elements of restriction and regimentation throughout the Victorian era, the mentally unwell could be detained in institutions and many were held without release as asylum populations soared. Although asylums can be defined as institutions existing for the care of mental health problems, by late 19th century, containment took precedence over treatment. Additionally, as populations soared, diversity of residents became more varied in terms of wealth and social standing.

(National Archives, 2020)

1913 Mental Deficiency Act

At the time of the Eugenics Movement, the mentally disadvantaged and struggling were to be cared for in communities, separate from society. Eugenics refers to a movement that is aimed at improving the genetic composition of society, part of doing so is the exclusion of the genetically ‘inferior’; those with illnesses and conditions such as of the mind.

(BPS, 2020)

1930 Mental Treatment Act

Moving towards greater autonomy those struggling mentally were enabled voluntary admission and treatment. This marked a turning point from the Lunacy Act 40-years earlier, individual responsibility and freedom was given greater recognition. Those struggling were perceived as patients as opposed to outcasts for the first time.

(Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020)

1959 Mental Health Act

Exemplifying a shift in power from judicial to medical, those struggling mentally were perceived more so as patients in need of support and treatment, as opposed to detainees. This was furthered by the 1983 Mental Health Act, giving medical professionals the authority to detain, assess and treat individuals deemed in need.

(The Health Foundation, 2020)

1983 Mental Health Act

The 1980s saw steps taken to move away from the mass institutionalisation of those experiencing mental health struggles, with an urge for care in the community. The 1983 Mental Health Act is one of the key pieces of legislation in-regards to outlining many processes followed through individual’s accessing services, such as referral and assessment. Though, individuals could be detained against their wishes if it was in the best interest for their own safety or the safety of others.

Identifying four legal categories for mental health struggles: mental illness; psychopathic disorder; mental impairment; severe mental impairment. A somewhat restrictive and reductionist view of mental health experiences.

(NHS, 2020)

2007 Mental Health Act

Moving away from individualised legal categories with an encompassing definition of ‘any disorder or disability of the mind’. A step towards recognising the diversity of mental health problems and experiences.

(The King’s Fund, 2008)

Throughout time there have been hundreds of institutions that have come and gone in the care of the individuals deemed in need of support. The original small-scale madhouses that assisted in separating the misfits from society made way for the rise of the asylum, with the hope of care and treatment dwindling in Victorian era regimentation and containment. Late 20th century saw the fall of the vast infrastructures that once housed thousands of residents as those struggling returned to the homes and communities they were once separated from. We live in an era where 1 in 4 people experience a mental health problem in their lifetime, the majority of whom continue to live their everyday existence and routine.

However, throughout history there have been notorious institutions in which individuals spent considerable time; some recognised for the worst of reasons and others marking a clear turning point in the housing and caring of the mentally unwell.

St Mary of Bethlem: Bedlam

St Mary of Bethlem was the first and arguably the most infamous of mental health institutions in England. Originally constructed in 1247 it opened doors to the ‘lunatics’ of the day by 1403 (Historic England, 2020, b).

(Google, 2020, a)

At the time there was much hysteria surrounding the mentally unwell and thousands would flock to Bedlam to spectate in awe at the “wonders” housed there. With a notoriously beautiful building and vastly growing reputation it was the amusement attraction of London. Residents of the institute could be found in cages and chained to walls much like captive animals. An account of a resident mentioned by Bragg (2016), tells the tragic story of up to a decade’s worth of confinement within an inhumanely cramped cage, due to the man’s wrists being too small for shackles. Highlighting the principles of restriction and punishment utilised at the time. Though there were cases in which patients were confined for the safety of themselves and others, the accounts of individuals spending years caged with little reprieve exemplifies the stark conditions.

Procedures undergone at Bedlam followed a structure of punishment and religious devotion. Treatments tailored to conditions included blood-letting, purging, and rotation therapy. Residents were often physically restrained and there was little in terms of support or nurture.

If you read about Bedlam you may be greeted by horrors highlighted at the time by William Tuke in the late 18th century cited in Havard and Watson (2017), testifying to the maltreatment at Bedlam. After an investigation was conducted, atrocities of abuse and inhumane treatment were brought to light. Despite outcry and shock relating to the horrors, questionable practises continued at Bedlam and many other institutions from the 13th century through to the late 19th century.

Though, a wave of new care-focused treatment and handling of the mentally struggling was introduced with the emergence of retreats such as that of York. Later followed by the rise of the asylum and a centralised approach to institutional running under the Lunacy Commission in 1835, pulling the likes of Bedlam further into line of better practise.

Bedlam’s doors were eventually closed in 1948.

York Retreat

With institutions such as Bedlam raising many controversial questions, a new era arose ushering in the prioritisation of care and treatment.

(Google, 2020, b)

Up until the early 19th century, much of the focus had been upon protecting society from the imposition of the insane. Those who struggled were deemed outcasts and potentially damaging to the order around them. However, following investigations and reports such as that of William Tuke’s and the 1815 Wolfenden Report, shifts were made towards the implementation of moral judgement and kindness.

The York Retreat was opened in 1796 as one of the first asylums marking the rise of hope for the care and treatment of the institutional residents, running as a non-profit sanctuary. Founded by William Tuke, the retreat was on a small scale with a community of around 30 residents. Principles of morality, humanity and community underlined the operations and running of the resident’s care. Although physical restraint and corporal punishment was disbarred, fear was utilised as a psychological tool in managing individuals.

Much of the institution reflected the values of a Quaker family and lifestyle with the superintendent as the head of the community. The atmosphere was far more personal and care was intimately nurturing.

The rise of the public asylum came with Victorian era Britain, partially reflecting the care and treatment approach of the retreat, though care later turned to confinement. By the end of the era, asylum populations averaged around 1000 residents with few ever released. The aim of mirroring the intricate environment of the retreat became submerged in the national effort to provide support, which resulted in overcrowding, poor sanitisation and a subpar quality of life.

The rise of the Victorian asylum dominated mental health infrastructure until the 1980s when the buildings that once stood with such conviction and presence were torn down or utilised for other purposes. Today there are mental health hospitals that can house residents whom pose a risk to their own safety or the safety of others, with the assumed end-goal of release back into the community when able to do so.

Confinement & Restriction

Restraint harness 1800s

Source: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/victorian-mental-asylum

Restraint collar 1800s

Source: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/victorian-mental-asylum

Restrain and confinement were some of the dominant approaches pre- late 19th century. In early institutions such as Bedlam, residents spent much of their time chained or physically restrained in some manner (Bragg, 2016). The principle focus was not the care nor treatment of the mentally unwell, but more so their segregation and detainment. Restraints, including harnesses and collars were later found in multiple institutions utilised across time.

Methods utilised as treatment during this time included purging (forced vomiting), and bloodletting (making an incision to release blood (Bragg, 2016). These methods peaked in the 1600s during which time it was believed that mental ill-health was associated with an internal imbalance, corrected through these methods.

Therapeutic and Medical Interventions

o The Talking Cure

Freudian principles developed by Sigmund Freud at the end of the 19th century marked the development of what is now recognised as psychotherapy. The utilisation of therapeutic conversation and a therapeutic relationship to uncover inner conflicts relating to our subconscious and past experiences. There was an acknowledgement that struggling mentally in the present could in fact be related to traumas and trials of the past and the unresolved conflicts.

o Insulin Coma Therapy

ICT entailed giving individual’s a series of injections to reduce their blood sugar to a level in which they would lose consciousness, followed by a glucose inject to revive them. The treatment carried significant risks with 1/100 patients losing their lives, despite this it was used steadily through to the 1950s.

o Prefrontal Lobotomies

One of the most controversial developments in recent medical interventions, the procedure involved the severing of nerves in the front area of the brain (prefrontal lobe). Considered a revolution in treatment at the time, tens of thousands of procedures were performed in the UK carrying the possible consequences of brain damage and severe impairment. Some positive outcomes were reported in-relation to reduced anxiety and lessening of violent outbursts, but these were severely outweighed by the costs. Lobotomies consequently declined by the 1970s.

o Electroconvulsive Therapy

ECT involves administering electrical current through the brain to induce seizures, whilst this sounds hideously controversial it is still a technique utilised in serious cases today such as major depression. The precautions and safety measures taken to ensure patient comfort throughout the procedure have come along way. Though, there are still potential costs relating to memory loss.

o Cognitive Therapy

Developed in the 1960s based on Aaron Beck’s understanding of the role negative thoughts play in-relation to negative mental health states. Outlining how individual’s responses to situations, how we perceive and process them mentally, contributes greatly to our overall mental wellbeing. Negative perceptions and thoughts create a negative cycle in which a negative feedback loop ensues. Cognitive therapy rests upon challenging these negative cognitive frameworks, using reason and logic to combat negative thoughts with examples and evidence. Later emerging as cognitive behavioural therapy, one of the most popular methods in working with depression and anxiety.

(For more on cognitive principles please visit https://www.theroompsy.com/psychology-mental-health-disorder/do-what-scares-you-do-it-again?rq=do%20what%20scares%20you and https://www.theroompsy.com/resources/whirlpools-of-negativity)

Pharmacological Dominance

The 1950s and 60s marked the dawn of the pharmaceutical and medical domination of mental health treatments with the development of drugs such as largactil, Thorazine, and lithium (Havard and Watson, 2017). Antidepressant (ADM) and antipsychotic drugs challenged the necessity to contain those that were struggling mentally; the medications provided a means of care and management that did not require institutionalisation.

There has been much controversy relating to the medicalisation of mental health, there are arguments that drugs simply minimise symptoms of conditions as opposed to treating, furthermore they carry potential side effects and can lead to dependency. Despite this, medications such as ADMs have become a greatly relied upon tool in helping individual’s - one of the most popular of which being selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

(For more on antidepressant medications please visit https://www.theroompsy.com/psychology-mental-health-disorder/antidepressants-and-the-biopsychosocial-approach)

As time has passed there has been growth in the understanding mental health alongside fluctuations in how individual experiences are managed and further developments in how conditions are treated. In the 21st century mental health has become more prevalent, perhaps in-part due to the greater recognition, but also related to the strains and stresses of the world we live in today. Whilst more people may have to face such challenges and experiences, there is still a sticky stigma attached to the labels worn by those who suffer.

Though, it is acknowledgeable that what was once viewed as abnormal, insanity has undergone a process of integration into everyday society. Szasz (1961) cited in Pilgrim (2017), outlines ‘the myth of mental illness’, highlighting how it is in fact our greater recognition and categorisation of mental health conditions that creates such suffering. Everyday mundane sadness or stress can escalate into depression and anxiety, if deemed so. Whilst there are differing opinions on how to perceive mental unrest or emotional challenges, slowly these experiences are becoming accepted as part of everyone’s lives.

As with all things, the area of mental health has changed through time, but one underlying continuity is the existence of suffering and challenge to our mental states. Whether it be deemed supernatural, lunacy, heresy, diagnosed illness or simply an emotional experience of life; all humans face moments where their mental wellbeing is tested.

As time continues, our perceptions and understandings of mental struggles will continue to evolve as they have done so much already. Looking forward we can be hopeful that with these changes, the acceptance and support for those of us facing struggles will continue to flourish.

References

The British Psychology Society (BPS) (2020), ‘Looking back: Mental deficiency – changing the outlook’ [Online]. Available at https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-21/edition-11/looking-back-mental-deficiency-changing-outlook (Accessed 5th October 2020).

Bragg, M. (2016), ‘Bedlam’, BBC Radio 4 [Podcast]. 17th March. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0739rfg (Accessed 7th June 2020).

County Asylums (2020), ‘The History of The Asylum’ [Online]. Available at https://www.countyasylums.co.uk/history/ (Accessed 30th September, 2020).

Google (2020, a), ‘Define Bedlam’ [Online]. Available at https://www.google.com/search?q=define+bedlam&oq=define+bedlam&aqs=chrome..69i57j0l7.2021j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 (Accessed 30th September, 2020).

Google (2020, b), ‘Define Asylum’ [Online]. Available at https://www.google.com/search?sxsrf=ALeKk03EeyWnLaW64sqeFUKDASqTgwXCOA%3A1601466032854&ei=sG50X9_uM5qi1fAPmfyl8Ag&q=define+asylum&oq=define+as&gs_lcp=CgZwc3ktYWIQAxgAMgkIIxAnEEYQ-QEyBQgAELEDMgIIADIFCAAQsQMyBQgAELEDMgUIABCxAzIFCAAQsQMyBQgAELEDMgUIABCxAzICCAA6BAgAEEc6BggAEBYQHjoHCCMQ6gIQJzoNCC4QxwEQrwEQ6gIQJzoECC4QJzoECCMQJzoECAAQQzoFCC4QsQM6BQgAEJECUK2eEVjpsBFgsL0RaAZwAngCgAGGAYgBlwuSAQQxMi40mAEAoAEBqgEHZ3dzLXdperABCsgBCMABAQ&sclient=psy-ab (Accessed 30th September 2020).

Havard, C. and Watson, d, K. (2017), ‘Historical overview’, in Vossler, A., Havard, C., Pike, G., Barker, M-J. and Raabe, B. (eds) Mad or Bad? A Critical Approach to Counselling and Forensic Psychology, London, Sage Publications Ltd, pp. 23-36.Historic England (2020, a), ‘A History of Disability: from 1050 to the Present Day’ [Online]. Available at https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/disability-history/ (Accessed 25th May 2020).

Historic England (2020, b), ‘From Bethlehem to Bedlam – England’s First Mental Institution’ [Online]. Available at https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/disability-history/1050-1485/from-bethlehem-to-bedlam/ (Accessed 25th May 2020).

National Archives (2020), ‘Asylums, psychiatric hospitals and mental health’ [Online]. Available at https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/mental-health/ (Accessed 5th October 2020).

NHS (2020), ‘Mental Health Act’ [Online]. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/using-the-nhs/nhs-services/mental-health-services/mental-health-act/ (Accessed 5th October 2020).

Pilgrim, D. (2017), ‘Diagnosis and categorisation’, in Vossler, A., Havard, C., Pike, G., Barker, M-J. and Raabe, B. (eds) Mad or Bad? A Critical Approach to Counselling and Forensic Psychology, London, Sage Publications Ltd, pp. 51-62.

Royal College of Psychiatrists (2020), ’90 years ago: The Mental Health Treatment Act 1930’ [Online]. Available at https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/blogs/detail/history-archives-and-library-blog/2020/09/09/90-years-ago-the-mental-treatment-act-1930-by-dr-claire-hilton (Accessed 5th October 2020).

The Health Foundation (2020), ‘The Mental Health Act 1959’ [Online]. Available at https://navigator.health.org.uk/theme/mental-health-act-1959 (Accessed 5th October 2020).

The King’s Fund (2020), ‘Mental Health Act 2007’ [Online]. Available at https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/briefing-mental-health-act-2007-simon-lawton-smith-kings-fund-december-2008.pdf (Accessed 5th October 2020).