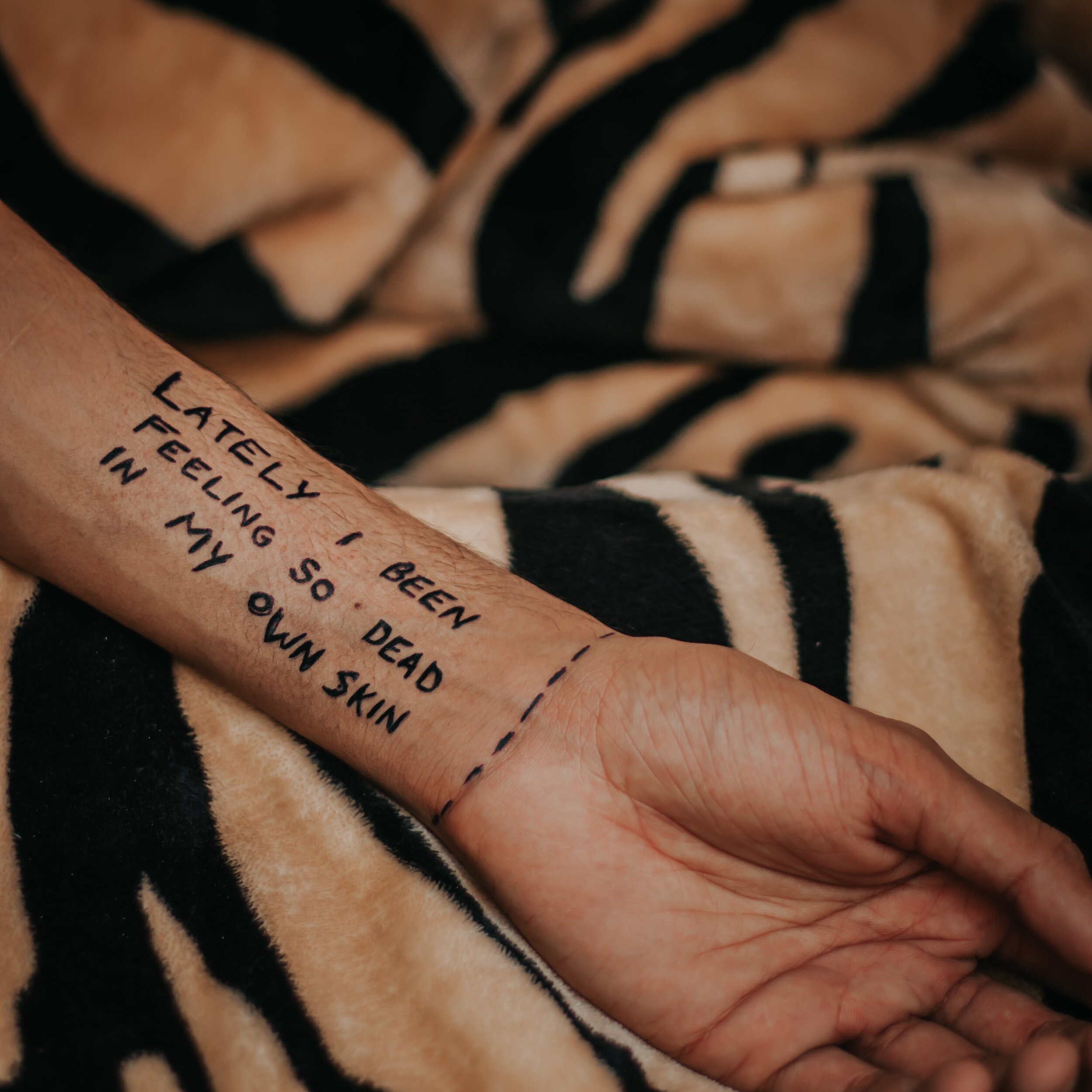

Is Social Media a Risk Factor for Deliberate Self-harm Among Adolescents?

This has huge clinical implications as self-inflicting injury is a common method preceding suicide and is the second leading cause of death for young people

By Mariam Adeniji, Featured Writer.

Deliberate self-harm (DSH) can be described as intentional yet non-fatal self-inflicted injury (such as cutting, an overdose of drugs or poisoning) irrespective of suicidal intent (Dyson et al., 2016). These behaviours are prone to repetition which can, unfortunately, lead to suicide if untreated (Hawton, Rodham, Evans, & Weatherall, 2002). The incidence rate of self-harm in the UK is estimated at 37.4 per 10,000 for females and 12.3 per 10,000 for males aged 10-19 years (Morgan et al., 2017). The prevalence among adolescents is estimated at 15.5% for 13-18-year olds within the community (Morey et al., 2017). However, there have been several issues when establishing the incidence and prevalence in this population group. The main issue being the various definitions of the term self-harm being used in studies and measurement scales; some include suicidal intent while others do not. This means that some participants may be conflicted as to whether their self-inflicted injury would be considered as one if there was no suicidal intent. Also, research in this area tends to include large female cohorts which can bias the findings. Both issues can lower the true incidence and prevalence of self-harm among adolescents. This has huge clinical implications as self-inflicting injury is a common method preceding suicide and is the second leading cause of death for young people aged 15-19 years of age (Patton et al., 2009). Therefore, it is important to investigate the possible risk factors that may influence an increase in self-harm in this group for prevention purposes.

Evidence suggests that social media use is increasing among adolescents who self-harm. It suggests that they spend more time on social media platforms (e.g. Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat etc.) than their peers who do not self-harm (Mitchell & Ybarra, 2007). The literature suggests that those who self-harm use social media to engage in conversations with others and use this to seek further information about methods of self-harming which in turn creates online communities (Mitchell & Ybarra, 2007; Dyson et al., 2016). Therefore, social media use can be a risk factor for adolescents who self-harm. However, it is not clear whether social media use is a risk factor which precedes self-harm in adolescents. This is due to the majority of the literature focussing on descriptive cross-sectional studies but not longitudinal studies (Dyson et al., 2016). Additionally, some population studies found that using social media daily is not associated with suicidal behaviour (Sueki, 2015). This shows that it is not clear which components of social media increases the likelihood of DSH e.g. increased use or its content. Nonetheless, some studies have found that social media can have benefits as adolescents are able to communicate their distress and seek help. With most quantitative studies only focussing on the negative influences of social media on those who self-harm, this can overemphasise its detrimental effects, therefore highlighting bias (Marchant et al., 2017).

In order to minimise the burden of self-harm on adolescents, comprehensive strategies are needed on a universal (adolescents), selective (risk factors that increase an adolescent engaging in DSH) and indicated (adolescents who have engaged in DSH behaviours) levels:

Universal: Advertisements on social media and the mental health benefits associated with decreasing one’s social media use or further moderation of self-harm content on social media (Chou et al., 2009).

Selective: School-based interventions such as coping strategies for adolescents with parents with psychiatric conditions, those who have experienced cyberbullying/bullying or those with complex family structures (Arbuthnott et al., 2015; Aschan et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 2012).

Indicated: Females aged 13-16 years of age have an elevated risk of engaging in DSH behaviours therefore increased use of social media can increase this risk. Therefore, formal and online support groups may be beneficial and teaching parents about moderating their children’s social media use and its content.

It is important to consider these preventative strategies on an individual and population level but also an economic level, as this prevents excess costs to secondary care services as increased prevalence of DSH in adolescents can increase hospital admissions.

If you are struggling with social media and would like to work on lessening its presence in your life, check out our 30 Day Challenge ‘Nocial Media’.

To learn more about the wider impact of social media on society, culture, politics, relationships, mental health, and concerns for the future, we recommend the documentary ‘The Social Dilemma’ (available for streaming on Netflix).

If you’ve been affected by the topics in this article, or know someone struggling with mental health issues, self-harm, or thoughts about suicide, contact any of the following help and support services:

Samaritans

Website: Samaritans // Call: 116 123 // Email: jo@samaritans.org

SHOUT UK

Text: “SHOUT” (or “YM” if you’re under 19) to 85258

Mind

Call: 0300 123 3393 // Text: 86463

Harmless

Email: email info@harmless.org.uk

Self-injury Support for Women & Girls

Website: Self-injury Support // Call: 0808 800 8088 // Email: tessmail@selfinjurysupport.org.uk // Text: 07537 432444 // Webchat

Young Minds

Website: YoungMinds Parents Helpline // Call: 0808 802 5544

National Self Harm Network Forums

Website: National Self Harm Network forums

References

Arbuthnott, A.E., & Lewis, S.P. (2015). Parents of youth who self-injure: a review of the literature and implications for mental health professionals. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9 (35). doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0066-3.

Aschan, L., Goodwin, L., Cross, S., Moran, P., Hotopf, M., Hatch, S. L. (2013). Suicidal behaviours in South East London: Prevalence, risk factors and the role of socio-economic status. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150 (2), 441–449. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.037.

Chou, W.S., Hunt, Y.M., Beckjord, E.B., Moser, R.P., & Hesse, B.W. (2009). Social Media Use in the United States: Implications for Health Communication. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11 (4), e48. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1249.

Dyson, M.P., Hartling, L., Shulhan, J., Chisholm, A., Milne, A., Sundar, P., Scott, S.D., & Newton, A.S. (2016). A Systematic Review of Social Media Use to Discuss and View Deliberate Self-Harm Acts. PLoS One, 11 (5), e0155813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155813.

Fisher, H.L., Moffitt, T.E., Houts, R.M., Belsky, D.W., Arseneault, L., & Caspi, A. (2012). Bullying victimisation and risk of self harm in early adolescence: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ, 344 (2), e2683. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2683.

Hawton, K., Rodham, K., Evans, E., & Weatherall, R. (2002). Deliberate self-harm in adolescents: self-report survey in schools in England. BMJ, 325 (7354), 1207-1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1207.

Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart, A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2017). A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 12 (8), e0181722. doi: doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181722.

Mitchell, K.J., & Ybarra, M.L. (2007). Online behavior of youth who engage in self-harm provides clues for preventive intervention. Preventive Medicine, 45 (5), 393-396. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.008.

Morgan, C., Webb, R.T., Carr, M.J., Kontopaantelis, E., Green, J., Chew-Graham, C.A., Kapur, N., & Ashcroft, D.M. (2017). Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self-harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ, 359, j4351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4351.

Morey, Y., Mellon, D., Dailami, N., Verne, J., & Tapp, A. (2016). Adolescent self-harm in the community: an update prevalence using a self-report survey of adolescents aged 13-18 in England. Journal of Public Health, 39 (1), 58-64. doi: doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdw010.

Patton, G.C., Coffey, C., Sawyer, S.M., Viner, R.M., Haller, D.M., Bose, K., Vos, T., Ferguson, J., & Mathers, C.D. (2009). Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. The Lancet, 374 (9693), 881-892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60741-8.

Sueki, H. (2015). The association of suicide-related Twitter use with suicidal behaviour: A cross-sectional study of young internet users in Japan. Journal of Affective Disorders, 170, 155-160. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.047.