Digging for the Pot of Gold at the End of the Spectrum

They were horrified to find their most promising student was going to be... a gardener! But autistics fit right in. It’s been my saving grace.

By Featured Writer, J E Rudd.

Gardeners are an odd bunch. We tend to be non-social animals a lot of the time; for whatever reason, we don’t want to work in a conventional office or factory setting. Sometimes, a career choice may be affected by someone’s sexuality, appearance, or other ‘non-conventional’ attitudes, and in a world where people make value judgements, gardening is perhaps one of the jobs where this can be overlooked or ignored. No one really cares if the bloke mowing the lawn is covered in tattoos, but you might not expect it of a barrister. That tomboy you knew as a kid? She became a tree surgeon.

It’s not a universal truth that everyone in the profession is a bit ‘out of the ordinary,’ but autistics fit right in.

When I grew up in the Seventies, no one had really heard of autism. Even my dad, who had studied psychology at Uni, had only a vague idea of it. We knew I was well ahead of my peers intellectually, but that just meant I was clever - not that I thought differently or had any kind of emotional difficulties.

I’ve never bothered to have an assessment for autism, but in the late 2000’s, I worked as Head Gardener at a private special education needs school, where all staff had to have training in recognising autistic symptoms. It can be a little strange when you realise that the descriptions relate to yourself, and more recently I found a mirror image of some of my behaviours in a co-worker who was a diagnosed autistic. It is equally hard to be told to make special allowances for someone whose internal struggles are pretty much the same as yours.

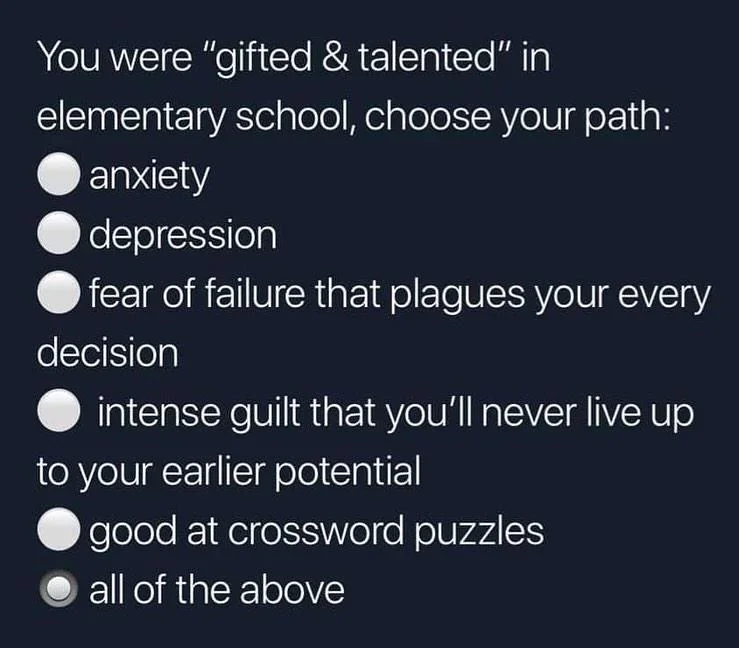

There’s a meme which probably applies to a lot of people, but which has even more resonance to a certain type of autistic, that says:

When I first read this, it brought back a clear memory of my Dad, frustrated at the end of the phone, trying to get me into a school for gifted children, only to find out that basically it was a non-starter if you didn’t have enough money to pay the fees. My school had published a book I wrote at the age of 12. I took English and Maths O Levels a year early, then completed the second year of O Level English Lit concurrently with the first year of A Level English Lit. I left school at 16 with a good number of O levels. They were horrified to find that their most promising student, destined to be the first person from that inner London comprehensive to go to University, was going to give it up to be… a gardener!

It wasn’t even an office job - even though I would still be studying, most people could not understand it. I was lucky that my parents, as always, backed me up. Incidentally, when I got my first Head Gardener job at a very prestigious private estate in London, my old Headmistress came to visit at one of the open garden days. She expressed how proud she was of me, when in actuality, she had never recognised the potential I had to do this job while I was at school. I’ve never regretted my decision not to do A levels, and going to Kew Gardens to study was better than University in my opinion.

I believe that working in the horticultural sector has been my saving grace. In my time, I have subscribed to ‘all of the above’ (if you swap Scrabble for crosswords) in the above meme. I suffered classic ‘burnout’, taking drugs and not going to work for 15 months due to depression. In the intervening years, anxiety, depression, fear of failure, and guilt have all reared their ugly heads from time to time, but I have learnt my own coping mechanisms and I now consider that I’m a reasonably well-balanced individual most of the time.

Being a gardener is not a job that most people consider a cause of anxiety, and for the most part, it isn’t. If you are at the lowest level on the rung, you just have to turn up for work every day and strim or mow or trim hedges, then go home at the end of the day. Physical ailments like bad backs or poor hearing are more likely than emotional issues. But if you start out as an apprentice, there are expectations and exams. I’m lucky that I never suffered from exam nerves, but as you progress up the ladder, there come responsibilities that may cause anxiety.

Will the bedding plants arrive on time?

Have I got time to water that shrub before it dies?

What if the mower breaks down again?

But the biggest cause of anxiety for me has always been dealing with other people, most often my colleagues or bosses.

A quick search on YouTube will provide you with any number of videos explaining common autistic spectrum traits. I’ve already mentioned a lack of social interaction, and gardening can provide plenty of opportunities for lone working. Another one that comes up frequently is being comfortable with repetitive tasks and needing a routine. I personally could double-dig for England if it were an Olympic sport. Eight hours a day, five days a week, for three months of the year, as proved by my placements at Kew Gardens, where every supervisor seemed to think he (they were all male) was giving me a unique opportunity to do something different.

There is something very transcendent about the routine of digging out trenches and filling them in again, such that the rhythm almost becomes like meditation. Other work, like leaf-raking or hedge-trimming, can have a similar effect. But gardening jobs do change throughout the year, so that many jobs only take place once or twice a year, albeit they may last for a few days, weeks or months. I have pondered the fact that although there is a routine and work can be repetitive, the routine evolves on a longer timescale than many jobs. It might seem too obvious a thing to state, but there’s a seasonality to garden work, so that you gradually start doing more and more of one task until it reaches a peak, then it tapers off again until the following year, for example, watering, mowing, and leaf raking. Thus, there might be a daily routine, but it is flexible, and the real routine is really only apparent year on year. The seamless transition between spring, summer and autumn jobs makes it easy to cope with change that in other circumstances might be drastic. It also helps that in gardening, multi-tasking is not often feasible, so tasks are usually completed one at a time with less need for processing different instructions. Dig, then rake, then plant.

One potential drawback for many autistics seeking to start a job is hypersensitivity. Bright lights, loud noises, and pungent smells can be an issue for some autistics. Gardening work is generally done in natural lighting conditions, with only a few exceptions, so that sudden bright lights are not usually a problem. As for noise, this is mostly due to garden machinery. While there are undoubtedly lots of irritating leaf blowers and other tools that need to be used, if you are the one making the noise and wearing ear defenders, you are in control of when it starts and stops, and protected from the worst of it. Quieter battery operated machinery is now becoming more common too. I’m not sure if the many perfumed roses and lilies that are grown are a problem in the same way that chemical and food smells can be; it has never been an issue for me. Finding out if a certain smell affects you may be a process of elimination, but there are lots of alternatives to scented plants.

Some other traits that are often linked to autism are Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Hyperfixation. Both can be positive assets in horticulture, in my opinion. Striping a lawn to perfection and edging it up perfectly is to be desired. Even laying out a bedding scheme or placing plants at correct bench spacing in a greenhouse is aided by a bit of OCD. Then there are plant names, which to most people sound like random noises or a case of glossolalia; there are actually very strict rules about the format of the names, and there’s a distinct pride in a certain breed of horticulturist in being able to rattle off Othiopogon planiscapus ‘Nigrescens’ or Euphorbia characias wulfenii, and even more if you can spell it right. The gifted child/crossword addict can be in their element learning all the names. It’s the botanical equivalent of knowing Pi to a hundred decimal places.

Hyperfixations are positively encouraged in hobby gardening in particular, although some obsessions get a professional vent in botanic gardens, such as cacti or carnivorous plants, it’s the amateur that takes the stage here. Growing exhibition gladioli or dahlias is not as popular as it once was, but vegetable competitions are still common, and growing giant vegetables is - pun intended - bigger than ever. You can’t tell me those guys who compete to grow pumpkins the size of cars and onions the size of beachballs are not hyperfixated. And that’s without mentioning the collectors: people who grow 300+ different maples in pots or galanthophiles (yes, that’s a thing), so obsessed with snowdrops that they will pay £1,850 for a single bulb. And what is amazing is that all this is considered quite normal in the world of horticulture. Eccentric, maybe, perhaps a little obsessive, but all perfectly acceptable.

The physical act of gardening, even for the non-autistic, can prove therapeutic against depression and anxiety. If you work from 7.30 – 4.30 doing a manual job, especially when it’s cold outside and raking leaves is about the only way to keep warm, you are generally tired enough to get to sleep without those annoying brain niggles. Not everyone has a Zen garden to rake the gravel in, but there are lots of jobs (maybe not using a chainsaw to fell a large tree) that allow you to process things while you are working. Another benefit is that of job satisfaction, although it is not always instantaneous. There’s something special in standing back and admiring your handiwork when you have neatly trimmed some topiary, which might have taken an afternoon, or constructed and planted a new border, which may have taken months, or watching a bedding display develop from tiny plants to a mass of spectacular floriferousness. The thrill of seeds you sowed germinating never goes away, no matter how many times you have done it. Watching the first crocus and daffodils emerge gladdens the heart. After the heat of summer, the autumn colours of the leaves bring a glow that reminds us that soon it will be time to light the fire. Thus, the changing seasons, watching the world change around us, and feeling connected to it, are a remedy for depression in themselves.

I am lucky that I chose a career that enabled me to do all this. Even if you don’t want to take up gardening professionally, gardening is the ideal hobby for all those ex-gifted children out there, a way through depression, anxiety, and guilt - and a great way to keep learning all your life.

P.S. If you don’t have a garden or an allotment, there are lots of opportunities to take up gardening as a volunteer. Some are Council funded, others are community groups and National Trust, English Heritage, etc use volunteers.

For more information on horticultural therapy, contact Thrive and if you are a professional gardener suffering from mental health issues, contact Perennial.