Do I Look Depressed in This?: On the Aesthetics of Mental Illness

Growing up amidst the 2010’s Tumblr era, I scrolled through pro-Ana sites, reposting skeletal girls with scars. Everything looked romantic, with a sepia filter and a Lana Del Rey lyric underneath. But as I started to exhibit symptoms that couldn’t be romanticised, such as anger or aggression, I was instead met with confusion.

By Cordelia Simmons, Featured Writer.

“How to drink through a straw without getting wrinkles!” a mechanical voice shouted at me from my phone.

I was performing a nightly ritual - lying horizontal and watching Tik-Toks. It’s a form of mindfulness, okay.

I scrolled past the woman selling anti-aging metal straws to another video. A sped-up version of Phoebe Bridgers’ ‘Motion Sickness’ soundtracked a girl who couldn’t have been more than sixteen, reading Sylvia Plath by a window. Later in the clip, she gets into bed, sunlight still blaring through her blinds.

‘DEPRESSION NAP LOOOOL’ a text bubble said.

She stirs, moonlight now peeking out from the grey clouds. Standing up, she changes in a mirror - her skinny, pale frame on display for a split second. She puts on an oversized knitted jumper, grabbing ‘A Little Life’ by Hanya Yanagihara. I sigh. I have my own personal beef with this book, believing it to be the kick-starter for years of the literary world’s exploitation of traumatic stories. But that’s a story for another day.

Underneath the video, the caption reads: ‘Day in the life of a Thought Daughter’.

Now, I felt old. What on earth was a thought daughter?

I typed the phrase into TikTok’s search bar, the results showing several videos with half a million likes. After twenty minutes of research, I discovered that the ‘thought daughter’ was an aesthetic encompassing a love for the arts, philosophy, and film, coalesced with intense emotions, anxiety, and melancholy. Picture teenage girls crying into the camera as Billie Eilish songs play and artful shots of SSRI packets underneath a poster of The Smiths.

I’d seen this before. As a teenage girl growing up amidst the Tumblr era of the early 2010s, I remember scrolling through photos on pro-Ana sites (blogs encouraging eating disorders), reposting photos of skeletal girls with scars on their forearms, and drinking green juice. Everything looked romantic with a sepia filter whacked over it and a line from a Lana Del Rey song copied underneath.

Tumblr was where I first learnt about feminism, about Angela Davis and Marsha P. Johnson. But it was also where I first learnt how to cut myself, a habit I struggled to beat until my mid-twenties.

I’d had a conversation with a friend recently who, like me, spent her nights as an adolescent scrolling these blogs.

“I can’t believe some of the stuff that used to slide on that app,” she said, pouring herself a large glass of wine.

I laughed, taking the bottle from her.

“I know. I used to think I was some femme fatale, but like, I was just depressed. I think I needed help.”

I rubbed the top of my glass with my thumb as I spoke.

“I’d really hoped this stuff had disappeared.”

A few days after stumbling across the Thought Daughter aesthetic, I opened TikTok to discover a new algorithm, one filled with teenage girls discussing their ‘grippy sock vacation’ - a term I later learned was a reference to a stay in a psychiatric hospital.

Image Source: https://share.google/images/tYUS1SDvgWaIzfypP

When I spent time in a ward at 23, a few of my fellow patients were given socks with sticky plastic on the bottom to make sure they didn’t slip on the linoleum floor. These were typically the women who were disoriented and confused due to their medication.

There were videos of girls in similar wards crying in their beds, being locked in the sensory room, and clips of psychiatric assessments. All with that same-old soundtrack - a slow indie-folk song.

I wondered more about the link between the Thought Daughter aesthetic videos I had watched a few nights prior and the clips I was being confronted with now. I realised that the issues my friend and I had faced as teenagers hadn’t disappeared at all. They’d simply evolved.

Creative depictions of mental illness have been around for centuries. Almost all our artistic ‘greats’ used sculpture, paint, or music to portray their experience with poor mental health.

In 2023, I spent hours entranced by the Yayoi Kusama exhibition at the Tate Modern - rooms full of mirrors and fluorescent lighting hanging from the ceiling, creating a surreal and eery environment. Kusama was known to depict the symptoms of psychosis she was experiencing through her immersive, structural art (Tagliabue, 2021). In an interview, she was quoted as saying: “My artwork is an expression of my life, particularly of my mental disease” (Turner, 1999).

Now, I’m not comparing TikTok videos to artistic geniuses such as Kusama, but the conversation around whether these short-form videos count as ‘art’ is one that is alive and well (Grothe, 2024).

But when does expression beget romanticisation?

Romanticisation typically occurs when something is described or portrayed as more attractive than it is in reality, usually through idealising positive aspects and downplaying negative ones.

This isn’t always bad. A good friend of mine takes photos daily of small things that bring her joy, saving them in an album on her phone titled ‘Romanticising the Daily’. It’s a practice that offers her a moment of reflection and presence in a city that is constantly moving.

But when we romanticise characteristics or traits of an individual, we step into dangerous territory. Often, a result of such romanticisation can mean a subtle dehumanisation - being seen as an ‘idea’ of a person, rather than an actual person.

I experienced this firsthand in my early twenties, during my years spent embodying the ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’ trope - a term coined by film critic Nathan Rabin, as a female character that teaches ‘broodingly soulful young men to embrace life’ (Rabin, 2007). As the trope evolved, many of its hallmark characters, such as Clementine from Michael Gondry’s 2004 film ‘Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind’ (Gondry, 2004) embodied traits common in mental illnesses such as Borderline Personality Disorder. Crucially, these symptoms were packaged in a fearless, whimsical way, rather than something that might need psychiatric intervention.

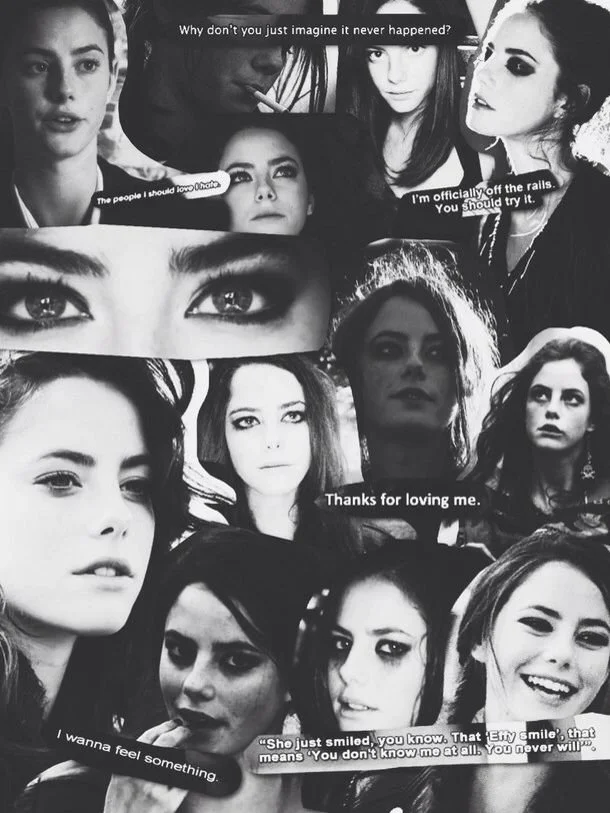

Men told me how endearing they found my lack of boundaries, how cute I was when I lay in bed all day. One man even compared me to Effy from the TV show ‘Skins’ - a character whose arc involves a psychotic break and a suicide attempt (Skins, 2009).

Image Source: https://share.google/images/Ym6nis4ZjD7M25F3m

“She’s so sexy,” he said.

But as soon as I started to exhibit symptoms that couldn’t be romanticised, such as anger or aggression, I was met with confusion.

“You’re not who I thought you were,” they’d tell me.

There’s no doubt that romanticisation can help us feel seen. But this process creates a mirage of acceptance for symptoms, one that has the potential to downplay the severity of our experience.

Both romanticisation and aestheticisation often go hand in hand with marketing, especially when done so on online platforms like TikTok. Some products have become synonymous with this ‘sad girl’ or ‘thought daughter’ aesthetic. I only wanted a Stanley Cup because I’d seen an influencer describe it as the ‘perfect bed-rot companion’. Some brands are capitalising on the mental health crisis more explicitly, creating quippy mental health-related one-liners for hoodies and t-shirts (MacDonnell, 2023).

When we simplify individual characteristics into aesthetics, we can’t detach them from the cultural and societal rules that govern what is deemed ‘cute’ or ‘marketable’ and what isn’t.

When discussing Tumblr with my friend, we noted the prevalence of thin, white women on our feeds. My new TikTok algorithm showed the same trend with creators such as Emma Chamberlain and Madeleine Argy (Valentine, 2024) - two thin, white women who post ‘relatable’ content detailing their symptoms of depression and anxiety - being hailed as voices of their generation. For me, my identity as a slim, white, cis woman played a huge role in meaning I fit the desirable ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’ mould.

Of all the ‘thought daughter’ videos I scrolled through, only two included a woman of colour. Of the ‘grippy sock vacation’ videos, all were white.

In a time where black women’s hair is 2.5x more likely to be seen as unprofessional (Dove and CROWN Coalition, 2023), and black women’s mental health is consistently not taken seriously due to prejudice (Ashley, 2014), it isn’t far-fetched to assume that the reason for their absence in these trends stems from racism that only offers thin, white women the ‘privilege’ of being romanticised.

A few weeks after I stumbled across the ‘thought daughter’ and ‘grippy sock vacation’ videos, I was sitting on a bench on Regent’s Canal with a friend who works in mental health.

“Do you think social media has been good for our mental health at all?” I asked him as a group of paddle-boarders floated past. “Like, do you think people have more information now?”

He sighed.

“It’s hard to say for definite, but I think people can find a sense of community online. Like they can learn more about a disorder they might have been diagnosed with. Obviously, there’s loads of rubbish out there at the moment, but I don’t think its wholly an evil thing. Just have to balance the good with the bad.”

God, he sounded smart.

Later that night, as I opened TikTok, a video popped up of a girl crying in a huge, expensive-looking car. After everything I’d reflected on in the last few weeks, my chest started to tighten, my breathing becoming shallow.

I stood up, putting my phone on charge in the corner of the room.

I was reminded of something my Pilates instructor always said to us at the start of a class: Take what works for you and leave the rest.