It’s Not You, It’s Me: Confronting my Inner Critic

Narcissists love nothing more than getting an emotional reaction from you that they can eventually exploit; hating to see a version of you that’s thriving. I decided to conduct some research into just how self-obsessed my anxiety was, starting with a confrontation of one of my most toxic habits.

By Featured Writer, Cordelia Simmons.

“Do you ever feel as if your anxiety is kinda a narcissist?”

I was sitting opposite a friend in a café on Broadway Market. Her hair was wet from our swim, and she smelt faintly of chlorine. We were underneath a tarpaulin rain-cover, and the drizzle was making a popping noise on the material as we sipped our coffees.

“I’ve never really thought about it,” I replied, wiping a bit of oat foam from my nose.

“Sometimes I feel like all my anxiety can tell me is that everyone’s talking about me, or everyone hates me, or that something I did was all anyone could remember from that party. It’s so horrible and self-obsessed. If a real-life person was like that, wouldn’t we hate them?”

I raised my eyebrows. For years, I’d been experiencing the same thing— anxiety that convinced me my friends loved nothing more than speaking about me behind my back.

I decided to conduct some research into just how self-obsessed my anxiety was, starting with a confrontation of one of my most toxic habits— surveying my loved ones on the regular to ascertain whether my anxiety was telling me the truth, that they did, in fact, all hate me. On my WhatsApp, over fifteen messages in the last five months included me asking a combination of two questions:

Do you hate me?

Are you annoyed at me?

Every one of those fifteen texts was after a social event— coffee, drinks, dancing. Times that I had felt free and happy, times where, dare I say it, I had felt loved - and there’s nothing a narcissist hates to see more than a version of you that’s thriving. My anxiety was rearing its ugly head to gaslight me into believing that a positive experience I’d just had was really a negative one. Not only this, but it was functioning under the guise that me, myself and I, were the main characters in my friends’ lives.

Just a few weeks before, I had cried to my boyfriend, committed to the idea that my friends were all secretly bitching about me because I’d forgotten someone’s name at a party the night before.

“I was so embarrassing,” I cried through thick gulps. “What if they all hate me because of it?”

My tears were staining his khaki t-shirt as he stroked my hair.

“You’re getting ahead of yourself,” he said. “Everyone was having a good time. They were too distracted.”

Of course, I knew struggling with anxiety didn’t make me a narcissist in the traditional clinical sense. In fact, anxiety can often make us more compassionate, more sympathetic, more in-tune with the world around us.

For me, my insecurities stemmed from a childhood spent with an emotionally abusive mother. I’d always known her to be intense—her moods operating in cycles I could never predict. Some days, we were two sparks of electricity, buzzing through the stagnant air. But most of the time, her words were harsh and sudden, the light drained from her eyes.

“No-one will ever love you,” she’d say. “I’m your mother and even I struggle.”

Years later, a therapist introduced me to the idea that my mother could have Narcissistic Personality Disorder (Mitra et al., 2021)— a mental health condition characterised by a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, a need for admiration and a lack of empathy. My mother was prone to many narcissistic traits— gaslighting (distorting my reality by convincing me I was lying), manipulation, usually in the form of withholding love and affection, and a general aim of destabilising my sense of self.

All things my anxiety had been doing for years.

Perhaps, my anxiety had morphed into a prototype of my mother, one that it seemed impossible to rid myself of. You can’t block your anxiety on Facebook.

But what if we were to take the same tactics used to reduce a narcissist’s power over you, and apply them to our anxiety?

In my early twenties, I was still in denial about my mothers’ potential condition, convinced that it was me that was the problem, not her.

In one session, a therapist recommended You’re Not Crazy- It’s Your Mother: Understanding and Healing for Daughters of Narcissistic Mothers, where author Danu Morrigan details her time growing up with a narcissistic parent, exploring her journey of recognition and healing.

Whilst not a clinical professional, Morrigan introduces some techniques to support the victim of narcissistic abuse, whether in cutting ties with the abuser, or reducing their impact on you. This was something I loved about the book— it acknowledged the fear and panic surrounding going no-contact with an abusive parent, rather than just assuming everyone would feel safe doing so.

Narcissists love nothing more than getting an emotional reaction from you that they can eventually exploit. I still remember the glee on my mothers’ face when her mind-games made me angry. Because, if I was angry, I was in the wrong. The narrative was hers. She was the victim.

To counter this, Morrigan presents a method known as grey-rocking, the term stemming from the idea that becoming as dull and unresponsive as a rock means your reactions can’t be manipulated. By refusing to engage with the narcissist, you are essentially giving them no fuel with which to start a fire. If they aren’t getting what they want from you, they’ll go looking somewhere else.

In practice, this may be giving simple, concise answers to probing questions, or masking emotional reactions. Before mustering up the courage to go no-contact with my own mother, this would sometimes look like:

“Your skin looks really bad at the moment, are you looking after yourself?”

“Yes, I am.”

Or:

“If you really loved me, you’d come home for Christmas. I guess I’m just such a bad mother.”

“I’ll think about it.”

Grey-rocking also makes you the worst possible audience for their self-involved tangents. By not responding to them with adoration or interest, you are essentially shutting down the conversation in a way that keeps you calm.

“You’ve already told me that story today,” I’d say. “I can’t have this conversation right now.”

In implementing grey-rocking with my mother, I noticed a difference not just in her interactions with me, but also with the interactions I had with myself. I blamed myself less. I started feeling strong after my conversations with her, not weak. Forcing myself to remain emotionless in the face of my mother’s actions meant I could see them clearly for the first time.

Ultimately, this realisation pushed me to make the bravest decision I’d ever made— the decision to stop contact with her. It took years but as I walked out of her house for the last time, I felt lighter, as if I was holding hands with the childhood me who had felt trapped.

A few weeks after the conversation with my friend, it was my 29th birthday— an evening surrounded by people who loved me, who wanted to see me happy, who wanted to spend their night celebrating me. My phone was full of photos of me smiling, dancing, laughing.

Predictably, I woke up the next morning questioning everything, regretting drinking those dirty martinis my friends had given me. As I lay in bed, Friends playing in the background, I had the same old conversation with myself.

“You were so humiliating last night. Everyone hates you. They’re just pretending to love you. How could anyone love you anyway? Do you remember when you made that joke and no-one laughed? They’re all talking to each other about you now. God, you’re such an embarrassment.”

I pulled the duvet cover up to my eyes, scrunching my knees up to my chest.

Okay, I thought. I have two choices. I can lie here all day, sprouting the same vitriol over and over again. Or I can try and see that abusive voice in my head as just that— an abuser.

“Everyone’s judging you.”

I took a deep breath— the kind my therapist had taught me, in for four, hold for four, out for four.

“Okay.”

“How could anyone love you?”

I shrugged, refusing to answer.

“You’re such an embarrassment.”

I moved the duvet cover to the side, grabbing a glass of water from my bedside table.

“You’ve already told me that story today.”

Gradually, the voice got quieter. It hadn’t disappeared but it sounded like it was under water— all muffled and warped.

As the weeks passed, I continued to use grey-rocking to confront my anxiety, and in a way, confront the version of my mother still existing in my head. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes it didn’t. But if I learnt anything from going no-contact with my mother, it was that it takes time. My anxiety isn’t going to vanish overnight. But maybe, just maybe, I can keep disengaging with that voice, until one day, I can walk away from it, lighter, prouder.

I still grab my phone automatically after leaving a social event, starting to write the words:

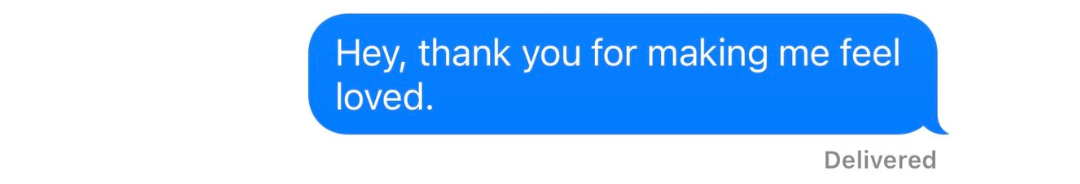

But sometimes, I look down at my screen and choose to type another message:

References

Mitra, R., Torrico, F., Fluyau, D., 2021. Narcissistic Personality Disorder. [online] Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556001/ [Accessed 27 August 2025].

Morrigan, D., 2021. You’re Not Crazy – It’s Your Mother: Understanding and Healing for Daughters of Narcissistic Mothers. London: Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd.